|

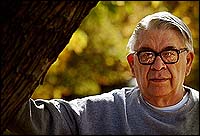

Vine Deloria Jr.

Native American scholar, activist and author Vine Deloria Jr. is receiving this year’s Wallace Stegner Award from the Center of the American West. His 1969 book, ‘Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto,’ helped put Indian rights into the national spotlight.

Date: Thu, 24 Oct 2002

Denver Post

NATIVE VOICE Tuesday, October 22, 2002 - The barrel-chested man on the sofa fires up an unfiltered Pall Mall, jets a blue cone of smoke toward the ceiling, and ponders out loud how it feels to be an icon staring down the barrel of a 70th birthday. "You always like to think you're younger than you are and still active," he says. "So when I started getting these lifetime achievement awards back in 1995, it came as a shock. I wondered, 'Do they know I'm going to die and rushed me up the list?"' He pulls on the cigarette, grins like a man not over-worried about showing up on obituary pages any time soon. When that time comes, the obit - at least the nutshell version - will read something like this: Vine Deloria Jr., award-winning writer, scholar and Native American activist; author of groundbreaking best-seller, "Custer Died For Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto." Deloria, with his iron-gray hair and chunky eyeglasses, remains very much with us. The 69-year-old Golden resident is this year's winner of the Center of the American West's Wallace Stegner Award. The honor is bestowed each year on someone who has made a sustained contribution to the cultural identity of the West. Deloria will be honored at 7 p.m. Wednesday in Boulder at the University of Colorado's University Memorial Center. Deloria seems gratified and amused by the attention. "If I sell five books these days it's a big deal," he says. "More and more, I go to conferences where people come up and say, 'My grandfather spoke highly of you.' "I even get people who ask, 'Didn't you used to be Vine Deloria?' I say I gave that up because it didn't pay. I'm just a little old man now." Which is not what he is at all. "He's a major figure in the history of the West," says John Echohawk, executive director of the Native American Rights Fund. "He's one of the most important Indian leaders we've ever had." Until Deloria seized the nation by its lapels in the late 1960s, Indians were viewed by many of their countrymen as ciphers rather than as a contemporary people facing issues such as education, jobs, health care and civil rights. Indians were images, suitable for decorating paintings, coins and Western movies, but scarcely viewed as a political entity. Deloria launched a dialogue with non-Indian America that helped change that perception. In November Deloria is due to travel to Albuquerque to deliver the keynote address at the National Indian Education Association's annual conference. "Issues change as generations change, but I've tried to stay out front with issues that will be of interest to future generations," he says. One project occupying his time is his effort to compile old federal documents and treaties that tribes can use in legal proceedings. Deloria lives with his wife, Barbara, in a split-level ranch house outside of Golden. The tree-ringed house sits beside a quiet dirt lane. A pale blue Ford pickup truck, crowned with a camper shell, is parked in the driveway. The father of three grown children, Deloria has been a granddad for 20 years. Along with their photos, his living room is filled with Indian pottery, rugs and weavings. Books are everywhere, including the mysteries that Deloria dives into whenever he needs to unplug his brain. Although Deloria's accomplishments are very much of his own making, his upbringing gave him a head start. A Hunkpapa Lakota born in Martin, S.D., he grew up in a distinguished family. His great-grandfather Francois Des Laurias ("Saswe") was a medicine man and leader of the Yankton Sioux's White Swan band. His grandfather Philip Deloria was an Episcopal missionary priest. His aunt Ella Deloria was a noted anthropologist; and his father, Vine Sr., was the first American Indian named to an executive post in the Episcopal church. After a two-year stint in the Marine Corps, Deloria earned degrees from Iowa State University and Augustana Lutheran Seminary in Illinois. He decided against a church career. Deloria felt it was not the most effective way to help his people. Deloria eventually broke from the faith he was raised in. "Christianity is a religion at the end of its rope," he says. "It's a religion that had to invade to convince rather than have people come to it." From 1964 to 1967 Deloria lived in Washington, D.C., where he served as executive director of the National Congress of American Indians. That period was the incubator for "Custer Died For Your Sins," the national bestseller that won Deloria fame and acclaim in 1969. He was 36 years old. "Indians were an unknown quantity," Deloria says. "There was a huge gap in how we were perceived by the average citizen and who we actually were. I had to be up front in the book, get the problems and politics out in the open." "'Custer' was really the impetus to changing the entire federal Indian policy," Echohawk says. Deloria became a high-profile presence. He was a go-to figure for anyone needing a What It All Means quote from a Native American. He testified for the defense at the 1974 Wounded Knee trial of activist Russell Means. But Deloria remained a scholar at heart. Being a public man and a private scholar can be a hard balancing act. "If you're going to do any meaningful work, you have to get out of the public eye and spend serious time in libraries," Deloria says. "That's where the important things happen." He still writes at a brisk pace. "Evolution, Creationism and Other Modern Myths," his latest effort, was just published. Three more books are in the works. He has published more than 20 during his career. Although retired from teaching posts at the University of Arizona and University of Colorado, where he taught history. Deloria serves on an array of boards. One of his causes is the Intertribal Bison Council, founded to improve the health of Indians by returning them to traditional foods. He also sits on the board of the National Museum of the American Indian, slated to open in 2004 in Washington, D.C. Deloria harbors mixed feelings about the project. "A museum suggests that a culture is a material thing," he says. "It suggests you can judge a people by the things they produced." No stranger to controversy, Deloria has raised eyebrows in recent years with views poking the scientific establishment: Petroglyphs suggest humans walked the Earth with dinosaurs. Older civilizations of intelligent beings were wiped out by cataclysms, leaving the Earth to rejuvenate in a cycle of destruction and recovery, which runs counter to the prevailing scientific notion of continuous evolution. Deloria lays out the ideas in books with provocative titles: "Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact," "Evolution, Creationism and Other Modern Myths." Such notions don't sit well with academia, which tends to treat them as contrarian at best and crackpot at worst. "I've always tried to take ideas that I found prevalent among traditional peoples and articulate them in a way that would be competitive with doctrinal views," Deloria says. "The audience for them is Indians and young non-Indians receptive to new views." So here he is, on the cusp of another award, comfortable in his skin and his nearly 70 years. He is asked about his legacy. It is a vexing question for a man with three books in the works. "That's really hard to say," Deloria says. "I've tried to help people, to help them stand on their own and realize they can stand on their own." Then he laughs. "But you know, when you make an omelet, there's always the matter of getting the eggs out of their shells." |

Vine Deloria was Philip's only son. He followed in his father's foot-steps, becoming a deacon in the Episcopal Church in 1913, and was ordained into the priesthood later the same year. The ordination was conducted at St. Elizabeth's, where his family lived for so many years.

Philip Deloria died on May 8, 1931, at age 77. The great Tipi Sapa belonged to the ages. One of the most distinguished leaders of the Episcopal Church, and a Prince of the Dakota Sioux, passed quietly into the pages of American history. Although a complete published history of Deloria has never been authored, sufficient documentation survives to certify to the importance and magnitude of his work. His name is prominent in many accounts of the missionary activities of the Church among the Sioux nation. The name of Tipi Sapa has also been relegated to an exalted place among the distinguished Indian brethren of Freemasonry.

He stands beside a small select number who have brought both honor and pride to their people and to our fraternity. At the head of that handful of names, three stand head and shoulders above the rest. They are Joseph Brant, Ely Parker, and Philip Deloria. As Deloria became the voice of the Dakota Sioux, so did Joseph Brant speak for the Iroquois nation. Among his accomplishments, General Ely Parker authored the text of the surrender document at Appomattox in 1865 in his role as military secretary to General Grant.

That troika of Indian Princes lived vastly different lives during their moment upon life's stage, but a common thread of Masonic brotherhood connects one to the other.

Ill JOSEPH E. BENNETT, 33°,was active in the Scottish Rite Valley of Cleveland before retiring to Texas in 1988. He now spends time writing for a number of Masonic publications.

Use your "BACK" buttom on your browser to return to former page!